He swapped the glamour of the music industry in the Big Smoke to return home and chronicle the fictional mean streets of no mean city.

Alan Parks may have come late to crime writing but his series is tipped to become an enduring classic of tartan noir with his hero, detective Harry McCoy, already been cited in the same breath as Rebus and Laidlaw.

But publication of the fourth novel in the Glasgow-set series – The April Dead, written in lockdown – is coloured by sadness as Parks, now 58, reveals his mother died just before Christmas.

And, on Mother’s Day, the author salutes Jean Parks, 87, for instilling in him his passion for Glasgow and says, without her influence, the series set in the city of his 1970s childhood may never have emerged.

The author – who moved back eight years ago – said: “My mum passed away just before Christmas. It was during Covid and she was in Erskine Care Home. It was a difficult period.

“Before Erskine she was in assisted living, that was around March, the last lockdown. You could go and wave in the window and that was really it. You were not allowed to go in because a lot of vulnerable live there. When she became less well she went to Erskine and they arranged for us to speak to her outside but she was in a wheelchair and she’d get cold. Erskine tried as hard as they could within the regulations to allow people to see their families, but it was very hard.”

Reliving the moment he and his older sister Janice Prowse, 63, said their painful final goodbyes, he told The Post: “At the end we could see her, but we had to wear PPE. It wasn’t the best situation. They had no Covid in Erskine but mum had dementia and it has a physical dimension. She just passed away.

“We were allowed to have 10 people at the cremation. My mum had a big family and she knew a lot of people – she was a very sociable person – so, although it was a perfectly nice ceremony, it was not the kind of funeral we expected. But you just have to roll with the punches in this situation.”

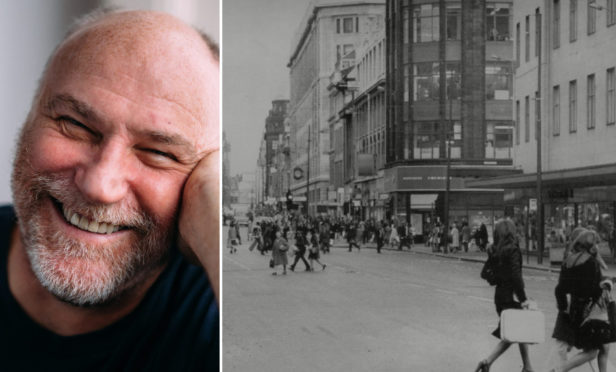

He remembered: “In the 1970s, when my books are set, I was 10. My mum was from Glasgow but we lived in Paisley. She had no interest in shopping there and every Saturday I’d get dragged off to Glasgow.

“I used to think it was a very glamorous place. I was excited. To me it was the big city. You’d see all sorts of different people, dressed-up young people, homeless people, rich people. I remember we used to go to Pettigrew’s and Frasers, the big department stores. It felt like another world.”

The writer says Glasgow, where the civic motto talks of a bird that never flew and a bell that never rang, has a glamour that never stopped fascinating him.

He said: “That was what I wanted to put in the books. I always think Glasgow is represented as a bit one-dimensional in fiction. So I wanted to make my fiction not just about this hard city, people battered down by life, and all that, but to try and say that – as much as now – Glasgow in the 70s had a lot of life and a had a glamour and excitement.”

His new book is set in April 1974 and the city is rocked by explosions. McCoy wades in when a bomb maker blows himself up, with few remains left to identify him. Meanwhile, a retired captain ropes the detective into finding his son, a sailor missing from the US naval base on the Holy Loch. The search leads him to the people behind the bombs as another, bigger explosion heads Glasgow’s way.

Parks – whose 2017 debut, Bloody January, propelled him onto the international literary crime fiction circuit and saw him shortlisted for the Grand Prix de Litterature Policiere, and whose third book, Bobby March Will Live Forever, was nominated for an Edgar Award – said of his new novel: “I wanted to write something about the American naval base. There used to be a submarine maintenance base at the Holy Loch just down from Dunoon.

“The Americans came on these huge boats that had space to take their cars. So, suddenly in 1970s Dunoon you’d see these enormous Cadillacs with huge fins parked next to a wee Minis. The Americans all looked tall with good teeth, slightly different to the Scottish people. They built a little town with shops and a bowling alley, it was quite a strange thing really and interesting to write about. I liked the idea of having these transplanted Americans wandering about.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, music pulsates through the pages of The April Dead. “I’ve put music in the books because a lot of musicians came from Glasgow – like Frankie Miller. The Glasgow Apollo venue is in one of the books.

“I listen to the music of the time of the book and make a playlist of what is relevant. In the latest book, Abba has just won the Eurovision Song Contest. I think if you put in it that Waterloo is on the radio, people will remember that. The character McCoy is complaining Abba is on the radio every five minutes. I’ve also been listening to some obscure Glasgow bands from that time.”

The former creative director of London Records and Warner Music says long nights in edit rooms working on music videos has imbued his writing with a sense of narrative and pace. He got into music scene when, as student of moral philosophy at Glasgow University, he met Lloyd Cole, who would form the Commotions. After graduating and without a job, he agreed to answer the band’s office phone in Glasgow while they were in London. It was a springboard to a 20-year music career.

“I commissioned the artwork and the videos and the photography,” he said. “Basically, you were trying to put the visual identity of the band together.” But the digital revolution and a subsequent collapse in the music industry led to redundancy and a return to Glasgow. Within days, however, bosses asked him to go back part time. He wrote this first book on the five-hour train journeys to London.

But when he reached 54 he decided it was time to find another career. He said: “It’s not a good idea when bands are young enough to be your children. One band referred to me as ‘Uncle Alan’ and I thought that was time to stop.”

His former London Records colleague-turned-author, John Niven, had light-heartedly suggested he write a book. Parks said: “He was horrified when he found out I had. I wrote it for myself and put it in a drawer.”

Niven offered to read the novel, liked it and passed it to his agent, who didn’t. “I thought that was the end of that, but he handed it to best-selling author Sarah Pinborough who sent it to another agent,” he said.

Now with three books under his belt and the fourth about to launch, his name is bandied in literary circles alongside those of William McIlvaney and Ian Rankin.

“It was Niven’s fault it got done,” laughs Parks. “I don’t know if he is happy about it or not, but there you go.”

Friends like Niven have been important to Parks in lockdown – he is single without children of his own, but counts himself lucky. “If you live on your own and write you are used to staring at your own space. It is a job you’re lucky to have in Covid, it’s harder for someone who works in a restaurant or factory. And the music industry is in real trouble just now.”

The writer has had to cancel a string of international book tours and festival attendances. And he admits: “I am missing having someone else make my dinner. I am sick of cooking. I just want to go to a restaurant. I don’t care if it’s the worst restaurant in the world. My cooking repertoire ran out nine months ago.”

And Parks can’t wait to get back to his watering hole, the McMillan in Shawlands. “I used to go there a lot. I sound like a miserable git, but I’d sit at the bar and read the paper.”

Just now, though, he is looking for inspiration for the next in the series, saying: “I tend to wander about Glasgow and find places I want to write about. I have been up in Royston, so some of it might take place there,”

And what would his late mum make of his work? “When my first book came out she didn’t have dementia. She said she wished there was less swearing and violence in it. She would have preferred a nice story where everyone was happy.”

The April Dead by Alan Parks will be published by Canongate on March 25

Sound & Vision

From Stephen King’s post-apocalyptic best-seller and a soul classic to small-screen mobsters and the cheering laughter of an old friend, Alan Parks shares a few of his favourite things

The book I can read again and again

The Stand by Stephen King, a post-apocalyptic dark fantasy novel first published in 1978 by Doubleday. I usually read it every couple of years and still enjoy it. It’s about a disease that leaves most of the world dead and the struggle between good and evil involving the few people that are left. I admit, it is maybe not the cheeriest book pick in these pandemic days, but it is a classic!

The song lyric that speaks to me

The best opening couplet of any song – the beginning of I Heard It Through The Grapevine, best sung by Marvin Gaye. “Ooh-ooh, bet you wondered how I knew, ’bout your plan to make me blue.” So simple, but so great.

My favourite movie scene

It has to be the opening scene of Apocalypse Now, the 1979 epic American psychological war film directed and produced by Francis Ford Coppola. I remember going to see the film at the ABC in Sauchiehall Street when it came out and just sitting there, stunned. Helicopter noises, forests exploding with napalm, an upside-down Martin Sheen and music by The Doors. It has it all.

My box set binge

The HBO series The Sopranos created by David Chase. It’s still, for my money, the best TV series ever made. It focuses on the late James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano: a husband, father and mob boss whose professional and private problems land him in the office of a therapist. It’s as much the story of a family, and how their relationships change over time as, it is about the Mafia. It’s addictive viewing. Another series I have just watched is ZeroZeroZero, an amazing story about the mechanics of how drugs get to America. The music by Mogwai is great, too.

My ultimate dinner party guests

Malcolm McLaren the former Sex Pistols manager credited with helping to form what became the legendary UK punk band. Tragically, he died aged 64 in New York after a battle with cancer and is buried in London’s Highgate Cemetery. He changed everything on the music scene and made music the most exciting thing in the world for me when I was growing up.

I’d also invite the late Andrea Dworkin, the American radical feminist activist, writer and critic whose ideas seem to be more relevant every day. Finally, it wouldn’t be complete without my friend, John Niven, the author and screenwriter. He makes me laugh more than anyone.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Kevin J Thomson

© Kevin J Thomson © David Magnus/Shutterstock

© David Magnus/Shutterstock © Steve Lyne/Shutterstock

© Steve Lyne/Shutterstock