IT’S June 28, 1928 and Scotland’s chief medical officer and his wife are welcomed by a nurse from Skye to open a new hospital.

Not that unusual except that it was 4000 miles from Scotland in the wild Appalachian mountains of America. Sir Leslie and Helen Mackenzie were opening the first Frontier Nursing Service (FNS) hospital and were greeted by Scots nurse Annie Mackinnon.

It was the culmination of hard work and determination by the hospital’s founder Mary Breckinridge, after she had visited Scotland four years earlier.

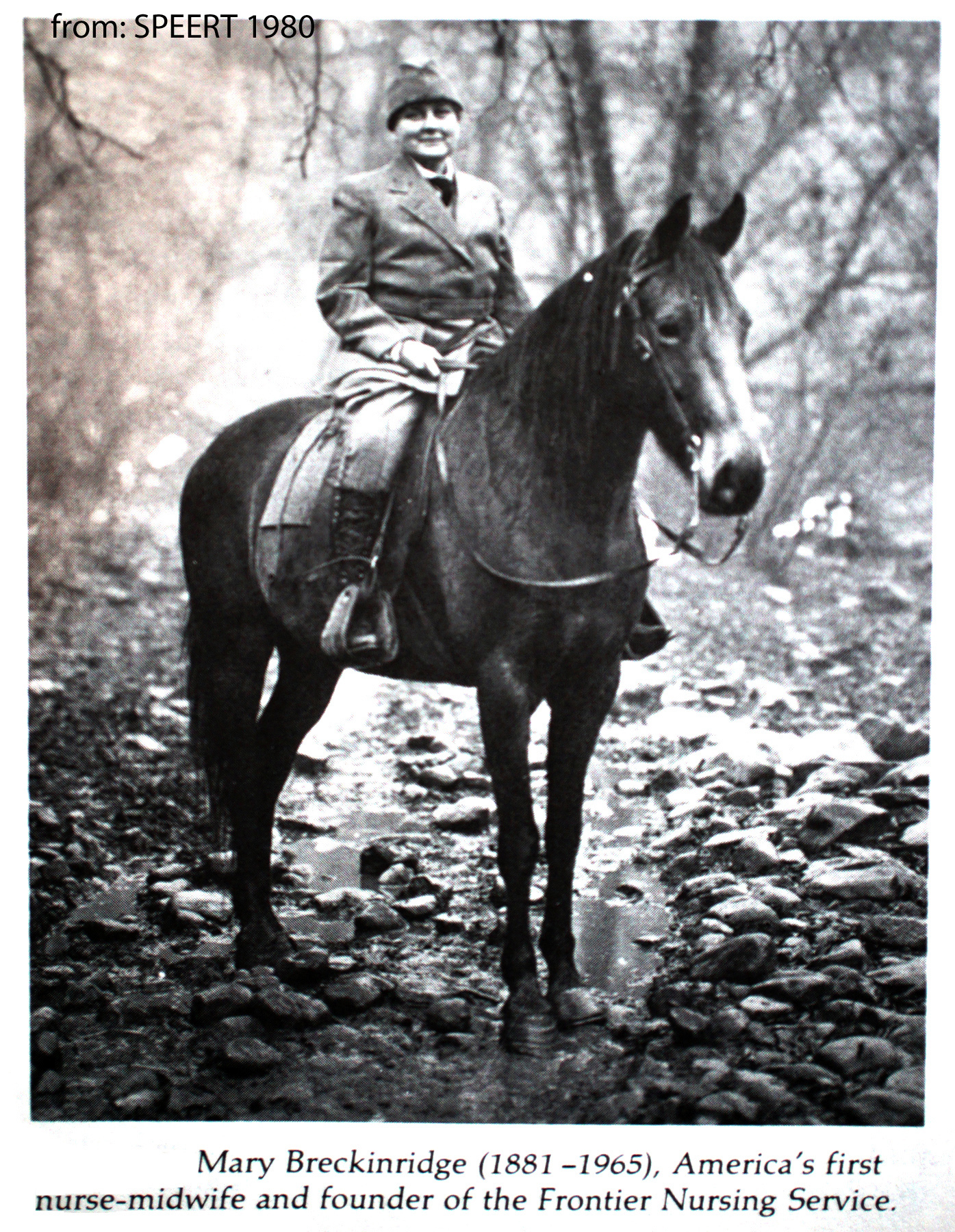

Born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1881, Breckinridge had lost both her children before they reached the age of five. She trained as a nurse in New York and later qualified as a midwife at Woolwich in London.

Breckinridge was impressed by the training of midwives in Europe and by the Highlands and Islands Medical Service. Established in 1913 to provide affordable health care to people in the crofting counties, it was a forerunner of the NHS.

The Mackenzies rolled out the red carpet when Breckinridge arrived in Edinburgh in 1924 before heading north. She later wrote: “Sometimes an experience is so deeply creative that you respond to it with everything that you have, not only in retrospect but at the time.

“When I went to Scotland in mid-August of 1924 to make a study of the Highlands and Islands Medical Service, I knew that weeks of enchantment lay ahead of me, but I could not know what it would be like to enter a strange country and feel at once that I had come home.” So she had. Her family had emigrated from Brechin in the early 18th century. She returned to America to develop the concept of the nurse midwife – based on the Queen’s Nurses she studied in Britain, providing not just care around births but also public health nursing looking after the whole family.

Unlike in Europe, there were no midwifery schools – the idea invoked hostility from doctors – and, by the 1920s, American women were twice as likely to die in childbirth than those under the care of Queen’s Nurses.

So Breckinridge advertised for British recruits to complement American midwives trained in Britain. The advert read: “Attention nurse graduates – with a sense of adventure! Your own horse, your own dog, and a thousand miles of Kentucky mountains. Join my nurse brigade and help save children’s lives.”

For some, the frontier life and Breckinridge’s domineering personality proved too much and they left. For others, it was an intoxicating challenge offering the freedom to live their own life and practise their profession without the stifling restriction and drudgery they left behind in the UK.

In some respects they were similar to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The Mounties always got their man but the Frontier nurse-midwives never left their woman once she had started labour.

But the work could be unrelenting and dangerous. Their horses could be unpredictable and covering the terrain was inherently hazardous. Mary Breckinridge herself broke her back in a fall from her horse in 1931.

The FNS continued to flourish however, and the foremost American health statistician recorded that, if the same service was available across the US, every year there would be 10,000 fewer mothers dying and 30,000 more children alive after the first month of life.

Opening that first hospital in the Kentucky mountains in 1928, Sir Leslie waxed lyrical in his address, saying: “It is a story full of adventure, sacrifice, passionate enthusiasm and splendid initiative. When Mary Breckinridge came to Scotland to see how we had faced a similar problem in nursing, we were filled with a new sense of significance of the work we had tried to do in Scotland.

“When, therefore, I was invited to give dedication of the hospital and nursing system in these mountains, I felt a glow of satisfaction that our work in Scotland had found an echo in the great spaces of America.

“The beacon lighted here today will find an answering flame wherever the human hearts are touched with the same divine pity.”

That beacon has continued to shine. The FNS lives on in the Frontier Nursing University and the experiences of district nurses in the Western Isles has recently been captured in Catherine Morrison’s book Hebridean Heroines.

After several decades Queen’s Nurses are now back, first in England and now in Scotland, demonstrating the same service and devotion to duty that their sisters did 90 years ago.

Chris Holme is a former Reuters Foundation fellow in medical journalism

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe