Long before DNA, the internet and even fingerprints, police mugshots were key to catching Scotland’s most-wanted criminals.Without central criminal databases, police in the 1800s and early 1900s relied solely on elaborate mug shots to help them snare offenders.

But images stockpiled by the fledgling forces back in the old days differ greatly from the police issue snaps we are used to seeing today.

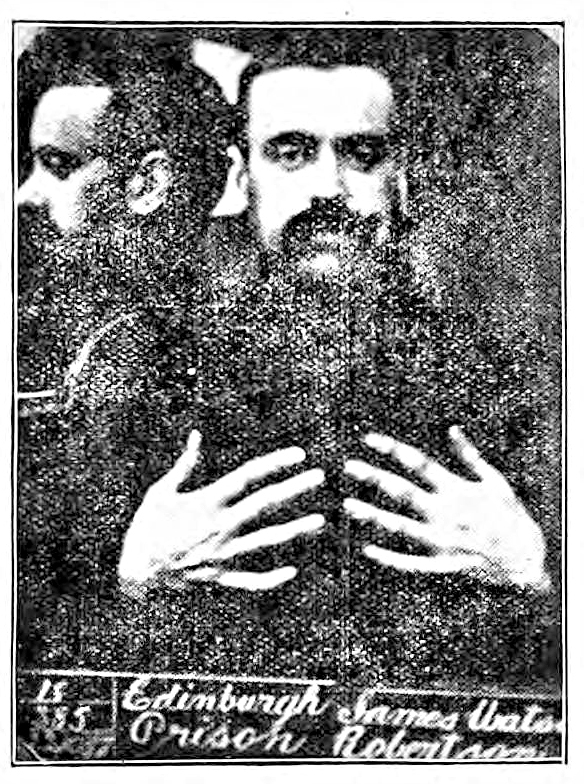

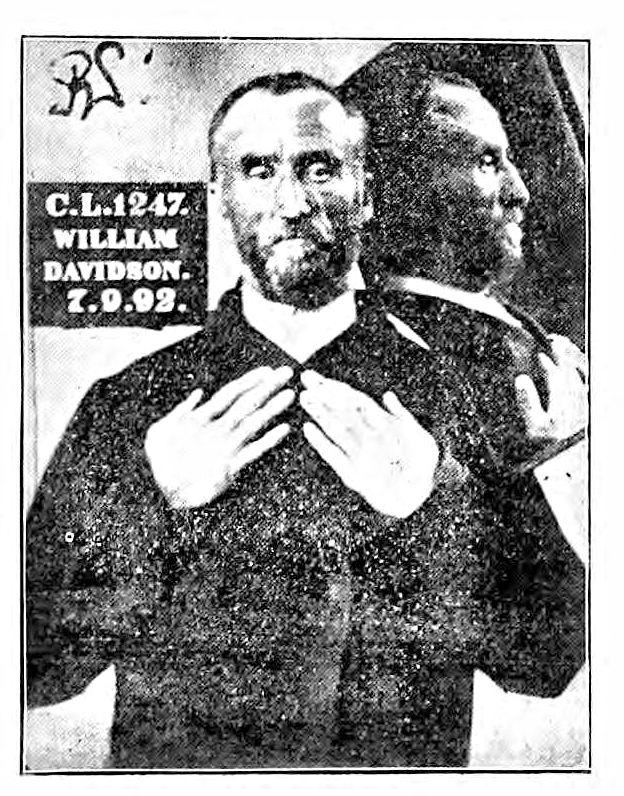

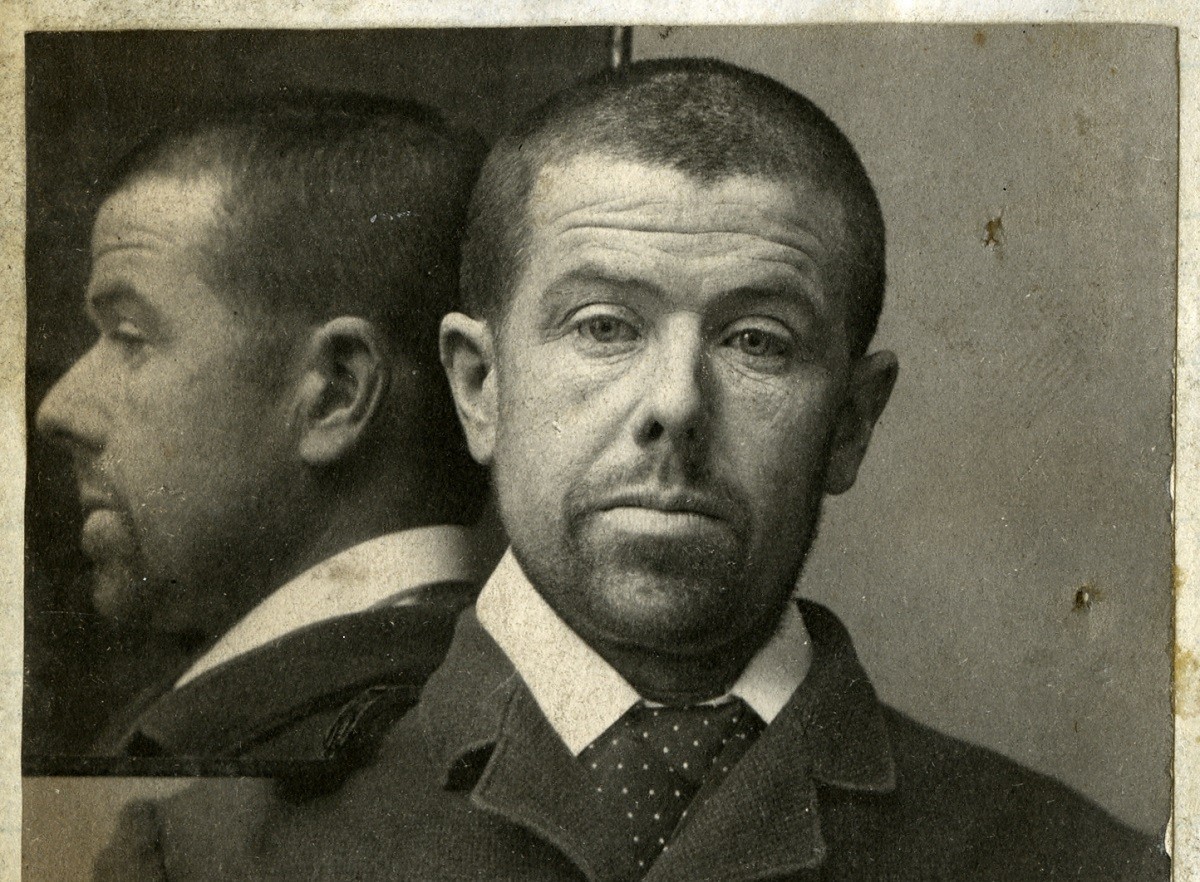

Because photography was expensive, early police photographers used positioned mirrors to capture crooks in profile and reduce the number of photographic plates they needed to use.

Criminals were also forced to put their hands on their chest to display their digits, as industrial accidents meant many ne’er do wells in those days were missing fingers.

“In those days the hands and face were the only parts of the body visible to the public, and there were more industrial accidents back then so suspects often had distinctive scars on their hands,” explained Glasgow Police Museum curator Alastair Dinsmor. They included detailed descriptions of fugitives and sometimes photographs or sketches, along with details of their crimes.

The motley bunch seen here have been pulled from the pages of the Police Gazette, a periodical used to circulate details of criminals in Victorian Britain, and the archive of Glasgow’s Mitchell Library.

After they were sent to jail, police forces would log criminals’ convictions, personal details, and known associates.The documents, complete with scrawled handwriting and grainy images of a bygone era, are seldom seen by the public, even though the archive is publicly accessible.

Mr Dinsmor added: “There were no fingerprints until the early 1900s and you couldn’t send more than a few lines over telegram, let alone a photograph,” he said.

“It was very important to share information, just like today, and police publications like the Gazette were the only ways for police to communicate around the country, it probably helped catch a lot of fugitives.”Mr Dinsmor said police used the Bertillon System, nine specific measurements of body parts that could be sent by telegram, to identify suspects until fingerprinting was widespread.

Police used photography in Scotland from about 1860 – but it was expensive so they would often use several mirrors to get different sides of a face in one shot.

The distinctive mug shots of the era often positioned the criminal’s hands just below their neck.“In those days the hands and face were the only parts of the body visible to the public, and there were more industrial accidents back then so suspects often had distinctive scars on their hands,” Mr Dinsmor said.However, he said even though police lacked the technology today’s forces take for granted, many of their tactics were similar.

“We don’t give Victorian police enough credit for using science and experts to fight crime,” he said.

“They were able to analyse bomb fragments to see who made them, or the printing on forged bank notes. We think of CSI as being a modern invention but they were good at it then.

“Still, most police work was old fashioned common sense – working informants, families and witnesses. Deduction and thinking outside the box was what made a clever detective.”

The records of more than 100,000 suspects from the Gazette, dating back 200 years, have been released online for the first time at Ancestry.co.uk.

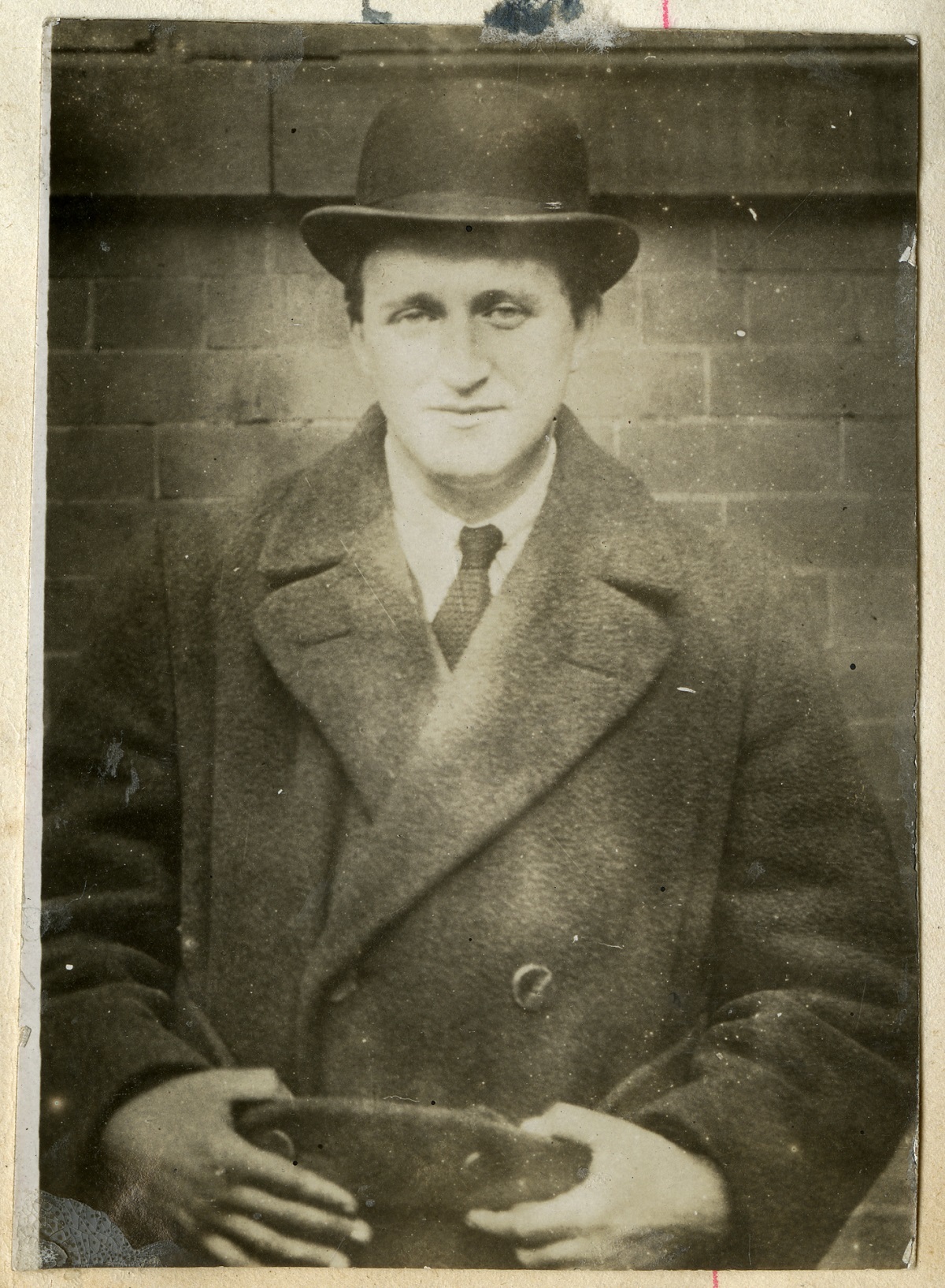

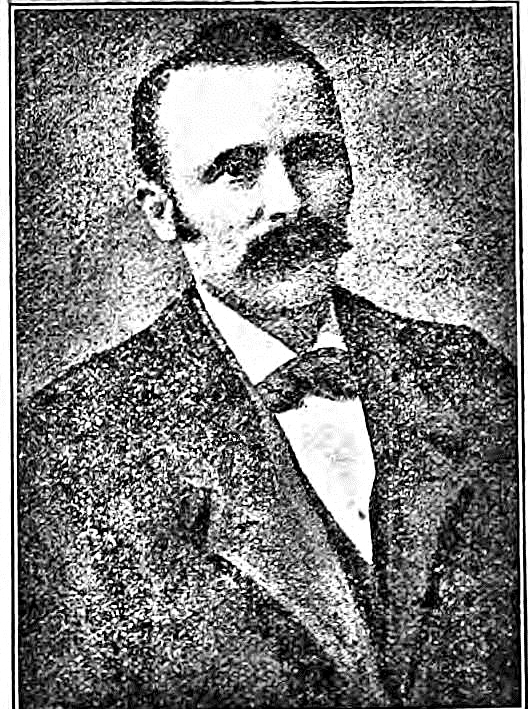

Robert Hendry

Hendry was one of two people tried and acquitted for the brutal murder of prostitute Sarah Brookstein, known and Sadie Brooks.

The crime, in October 1921, known as the Sword Street murder, was famous at the time and remains unsolved to this day.

The 33-year-old was found beaten to death with a claw hammer. in her destroyed and blood splattered Glasgow flat.

She had been tortured and a pair of pliers was embedded in her body, with a towel tied around her face to muffle her screams.

It was described by an expert at trial as “almost inhuman”.

Hendry was a pimp known for bullying prostitutes and was alleged to have killed Sadie at the behest of one of his girls who had “bad blood” with her.

He was allegedly seen lurking outside her 120 Sword St flat with blood on his forehead and getting on a tram with her the last night she was seen alive.

Hendry was found not proven at trial in February 1922 as he denied knowing anyone involved, a time of death could not be narrowed down from a week long window, and conflicting witness testimony.

The case is credited with shining a light on Glasgow’s grimy underworld.

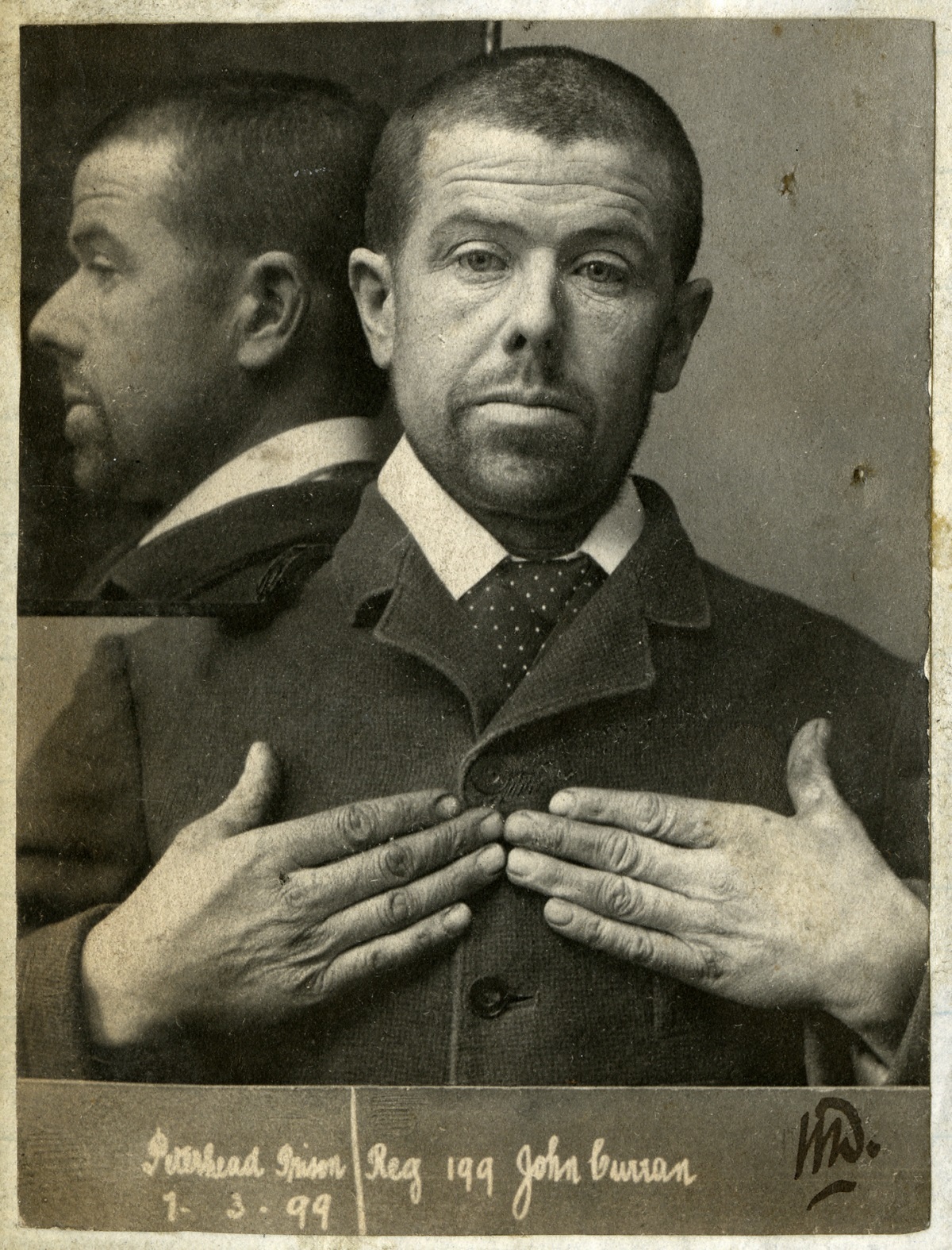

John Curran

The 35-year-old labourer from Glasgow was one of five Scots sentenced to death in 1899. though the ledger does not record details of whom he killed.

Curran was later spared the hangman’s noose and got life in prison instead.

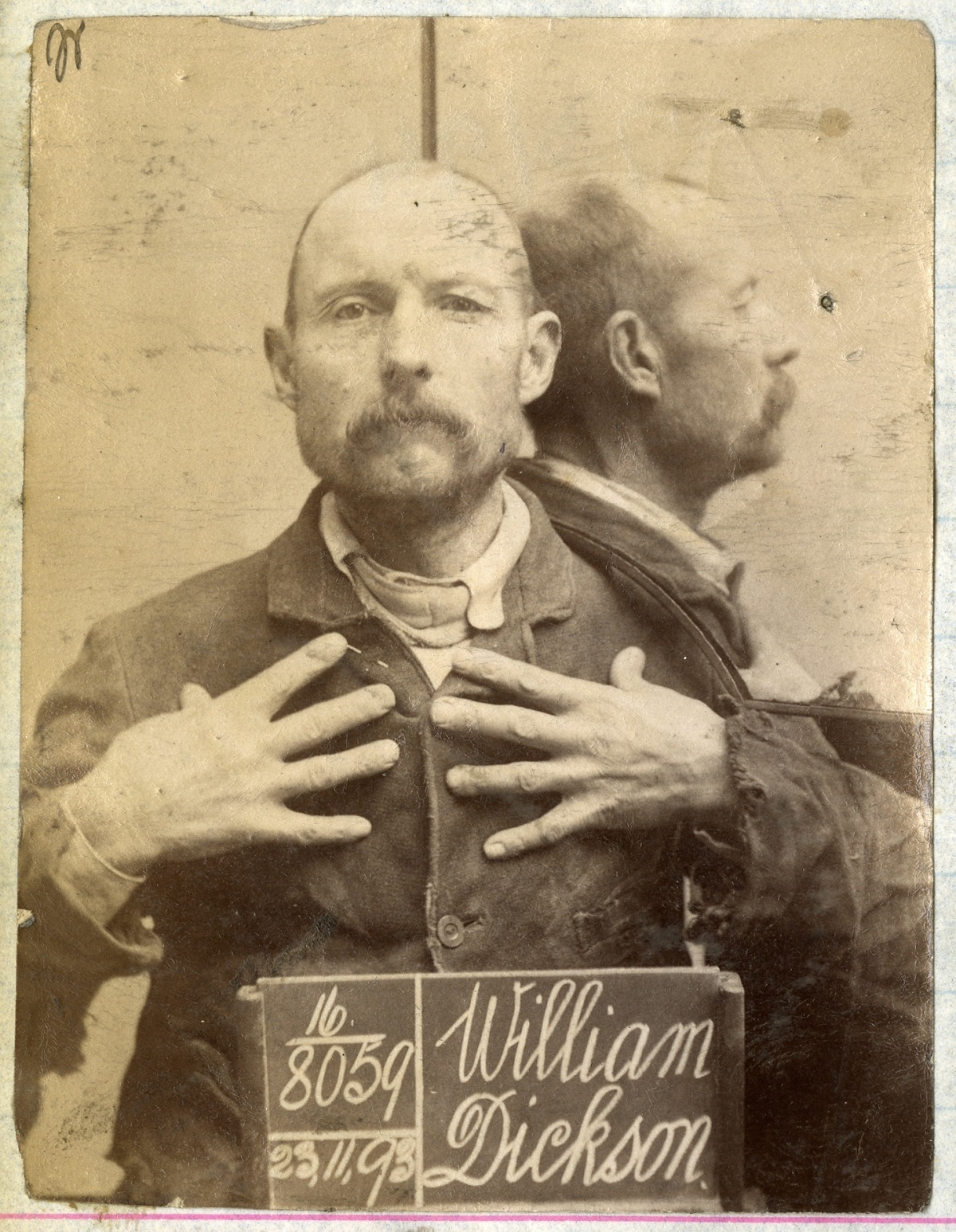

William Dickson

Dumbarton-born Dickson was a career criminal with a string of convictions. including theft, assault, robbery, and assault with intent to robin Glasgow, Stirling and his native Kirkintilloch, serving more than seven years jail.

He was identified by his long, narrow ears and a small hairy mole above his left buttock.

This image was taken after he was sentenced to three months behind bars in October 1893.

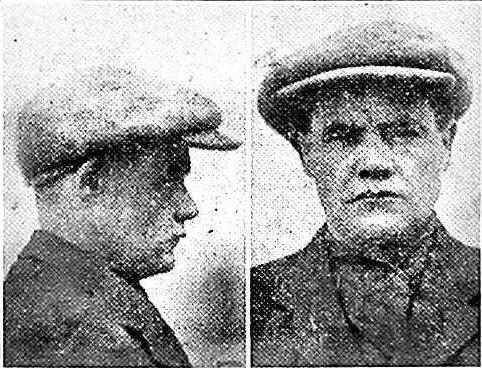

David Brodie

Brodie was given three horses to auction at market but only sold one – selling the other two on the side and pocketing the cash before disappearing.

His employer should have known better as the Perthshire based crook had convictions for indecent assault, larceny, fraud and embezzlement.

This image is from 1924.

George Gray

Wanted for embezzlement and forged bank notes totalling £233, the details of this Hawick hood were circulated in 1896.

He was said to have a deep voice. thin face and be well dressed with a silk hat.

He was a well-known commercial traveller for tweed and cloth firms.

A £10 reward was offered for information in an April 1896 edition of the Police Gazette.

Laurence Henderson

The police wanted Henderson so much they offered a £50 reward – one of the highest offered in the Gazette.

He had embezzled £2,000 from his company. and was thought to be trying to flee the country with it.

The Leith-based fugitive was pictured in 1900 and said to walk slightly bow-legged with a prominent nose.

James Watson Robertson

This scary-looking mug shot of the Dundee crook was circulated in 1900.

He had “Annie Love” tattooed on his forearm. and the point of his right hand little finger turned inwards.

He was wanted for fraud.

William Davidson

Davidson, pictured here in July 1899, was known to police as a serial robber and housebreaker. who had served more than 18 years jail and was now on the run again for another break-in.

The then 49-year-old from Linlithgow had collected a litany of injuries used to identify him, including a bent nose.

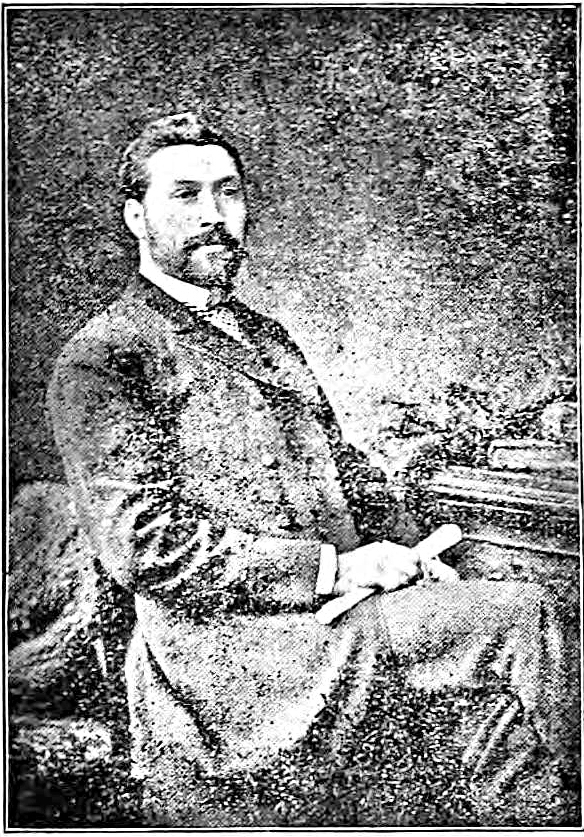

Alexander Peattie

Peattie seemed like a gentleman until hemade off with £7,300 in securities – almost £850,000 in today’s money.

He had a stoop and rheumatism had left him lame in his left leg with affected speech and “a clumsy, slouching gait”.

This mug shot of Glasgow-born Peattie was in the Gazette in February 1899.

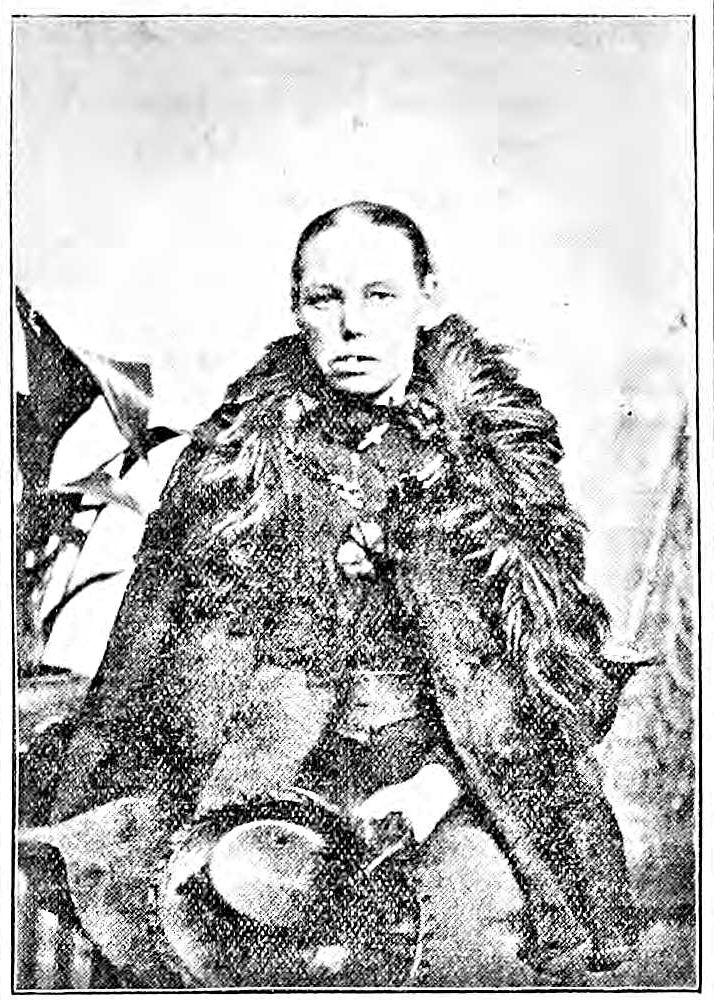

Catherine Brown

Police were hunting Brown for larceny in Greenock in 1899.

There were plenty of features to identify her including multiple missing teeth as seen in the photo.

She also had a four-inch scar above her right knee and a birthmark on her left shoulder.

The image dates from December 1899 and is one of many women in the archives.

READ MORE

Tina’s waist measures just 18 INCHES thanks to custom made corsets

Is Agatha Christie’s And There Were None the best crime novel ever?

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe