ARMISTICE Day will have an added significance this year.

On November 11, at 11am, we will mark the centenary of when the guns fell silent on the Western Front.

The armistice, signed between the Allies – Britain, France and the US – and Germany in a railway carriage at Compiegne, initially expired after 36 days, and a formal peace was only reached when the Treaty of Versailles was signed the following year.

And the armistice only covered the Western Front.

It took three days for the news to reach General von Lettow-Vorbeck in East Africa and a ceasefire to be agreed, and a further 11 days for him to formally surrender in what is now Zambia.

In January 1919, Hermann Detzner became the last German to surrender. An officer in the colonial security force in then German New Guinea, he’d evaded Australian forces for four years.

But on hearing of the armistice, he wrote to ANZAC command and offered his capitulation, surrendering in full uniform and flying the Imperial German flag at the head of his remaining troops.

After a brief stint in a POW camp near Sydney, Detzner was repatriated to Germany, where he received a hero’s welcome.

Five days after Detzner’s surrender, the Siege of Medina in modern-day Saudi Arabia ended when renegade Ottoman general Fakhri Pasha – who ignored direct orders from the Sultan to lay down arms – was arrested by his own men and handed to British-backed Arab forces fully 72 days after the official end of the war.

Now, I hadn’t heard of either of these “hold-outs”, despite studying the First World War at secondary school and university.

And despite the conflict having been gone over with a fine-toothed comb, and everyone knowing about the horror of the trenches, gas attacks and barbed wire, there are many aspects of the fighting with which people are unfamiliar.

So here are a few startling facts about “the war to end all wars”.

1 A Belgian battlefield explosion was heard in Downing Street.

Before the Battle Of Messines in June 1917, hundreds of miners toiled 100ft under Messines Ridge digging 19 tunnels under German trenches. Into these was packed 900,000lbs of explosives.

When they were detonated at 3.10am, the explosion – one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in history – obliterated much of the German front line and was heard by PM David Lloyd George 140 miles away in London.

2 I wouldn’t have been terribly safe during the war.

Only a handful of journalists risked their lives to report on the brutal realities of the war.

To control the flow of information from the front line, reporters were banned. Losses of warships weren’t acknowledged until after the war, for instance.

If caught, journalists faced the death penalty.

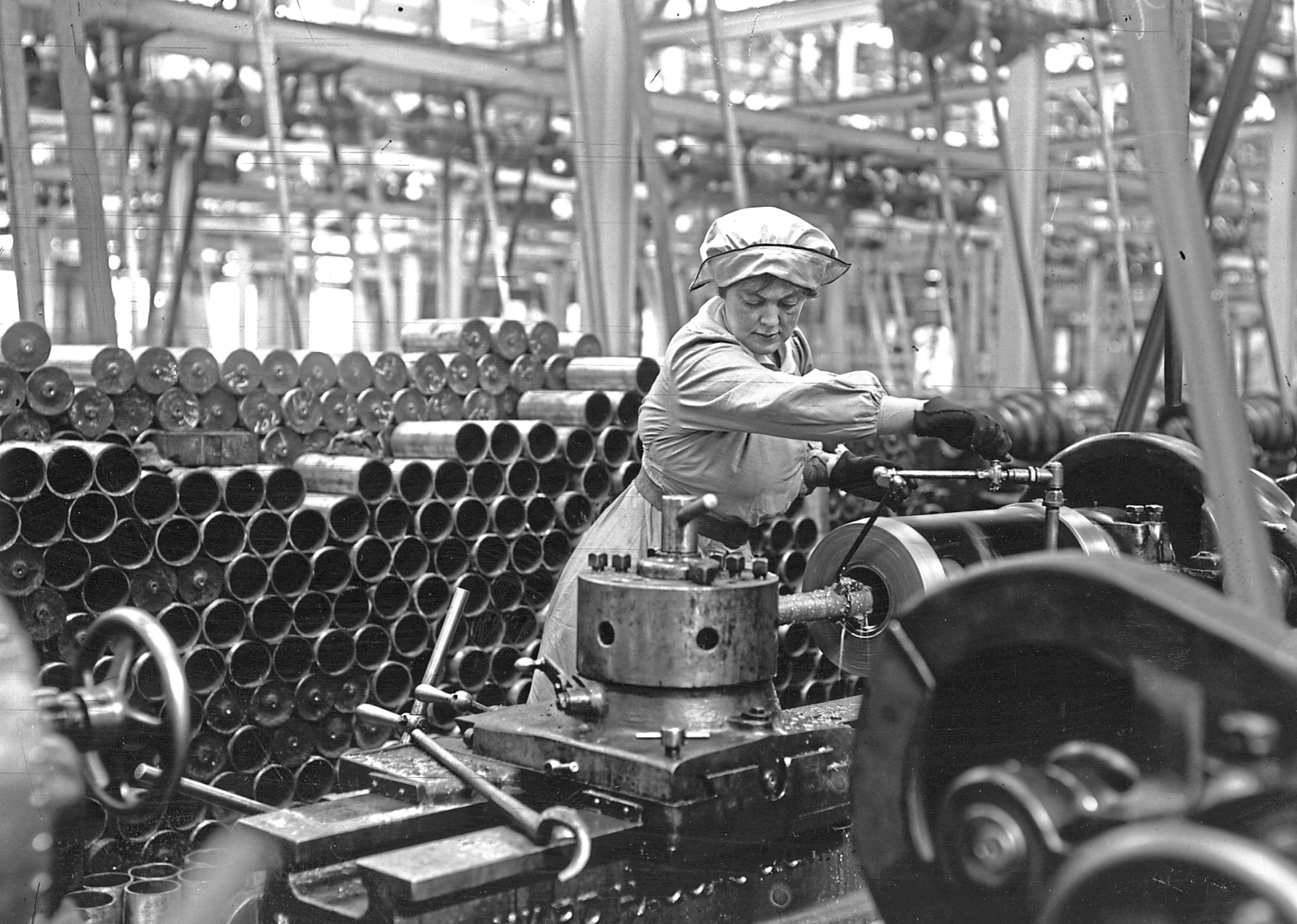

3 The war turned some women’s skin yellow.

With so many men called up, more than a million women entered the workforce, often working long hours with dangerous chemicals in shell factories.

Those who worked with TNT were often called “canary girls” because the yellow explosive stained their skin.

TNT is toxic to the liver, causing anaemia and jaundice, and 400 cases of toxic jaundice were recorded in “munitionettes”, of which 100 were fatal.

4 The First World War sparked the invention of plastic surgery.

More soldiers were wounded by shrapnel than bullets, especially around the face, and the twisted metal shards could cause devastating damage.

Surgeon Harold Gillies took on the task of helping disfigured Tommies, pioneering early facial reconstruction.

5 The youngest British soldier was a 12-year-old child.

The average infantryman was in his mid-20s and you weren’t meant to be sent to France until you were 19. But more than a quarter of a million underage soldiers fought in the trenches.

Sidney Lewis was just 12 when he lied about his age to join up. He would fight in the Battle of the Somme in 1916 with the Machine Gun Corps.

He was sent home when his mum sent his birth certificate to the War Office.

6 War is expensive.

The war nearly caused a financial crisis in Britain, which had been an economic superpower before the conflict.

It costs huge amounts to clothe, feed and equip an army, and much of what you pay for literally goes up in smoke – an astonishing £4 million worth of bullets were fired in a single day in September 1918.

7 Blood banks were developed during the war.

The British Army began the routine use of blood transfusion in treating wounded soldiers, with blood transferred directly from one man to another.

But US Army doctor Captain Oswald Robertson established the first blood bank on the Western Front in 1917, using sodium citrate to prevent blood coagulating and becoming unusable. It could be kept on ice for 28 days, then transported to casualty clearing stations for use in surgery.

8 Never mind battleship grey, ships got a colourful makeover.

With Germany keen to strangle Britain through U-boat warfare, it was vital to protect merchant ships carrying food and war material.

Norman Wilkinson, an artist and Royal Navy volunteer, came up with the notion of covering freighters in bold shapes and violent contrasts of colour.

The idea was that “dazzle” schemes would confuse German subs by making it harder to calculate their speed accurately, for example.

9 Nine out of 10 soldiers survived the trenches.

Actually being on the front line was quite rare for the more than five million British soldiers who served on the Western Front.

They were moved about the trench system to keep them away from enemy fire, only spending short stints in the very front lines. So the typical day for a Tommy would have been filled with boredom and routine.

The average battalion rarely spent more than five days a month in the line of fire.

10 Generals had to be banned from going over the top.

The stereotypical view of the British Army in the First World War is “lions led by donkeys” – brave men sent to die in their thousands by old buffers who sat out the war in comfortable chateaus miles from the front.

In fact, so many of the British top brass wanted to be closer to their men, they had to be banned from going into combat. Many were being killed, and the experience gained over the years it took to reach such high rank was too valuable to lose.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe